refugees

Monday, February 2nd, 2009by Rachael

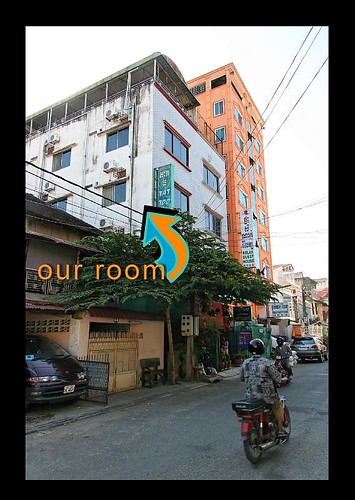

Hanoi, Vietnam

We had been expecting to hear a bit more English in Vietnam. Not sure what gave us that idea, but we had it all the same. And it was wrong.

In our few days at Vung Tau we met only a handful of people with ANY English at all. We managed to find rooms and food and bus tickets home again, relying entirely on sign language and rudimentary illustrations. We still don’t know why we had to go across town to the bus station to get a receipt on the day before travel and then pick up the actual tickets on the day. But we did it.

By the time we left VT we had picked up a smattering of food vocabulary – even a little language is empowering. It meant that on the train we could approach the dining car with some sense of confidence and ask, “Rice soup?” Cook’s head shakes.

“Noodle soup?” Head shakes.

“Rice?” Head nods.

“Beef?” Head shakes.

“Fish?” (seeing as I could see a big bowl of fish pieces sitting on the counter). Head shakes.

“Pork chop,” a young lady announces as she walks through the kitchen. That seems to be all the English she knows, and even then I’m a bit dubious – the pork is very very dark for pig! But it seems worth trying to find out how much.

“Dhong?” Cook holds up two fingers. I guess that means 20,000 for a plate.

Ordering ten is the next hurdle. Even with pointing to all my fingers, Cook will not believe I am asking for ten pork chops! So I point to myself and say, “Eight children.” Her questioning look indicates she has understood and the barrage of words that follow are accompanied by confirming smiles and handshakes. Cook collects ten takeaway containers and proceeds to fill them. Even a little language is empowering – without these few words we would have been limited to buying cans of coke and plastic containers of popcorn that we could point at on the refreshments cart.

Language-wise, we did this trip the easy way. Singapore, Malaysia, Bangkok….there was no need for anything other than English. In North Thailand we started to pick up some local lingo as we met people without English. By Laos we were in full swing and within a week there had enough words to communicate at the market and not feel totally alienated. On our return to Bangkok, we were able to learn even more Thai by trying out the very similar Lao we had learnt. In Cambodia we started over again, this time with Khmer. Greetings, numbers, the word for children, yes, no, food items…….

Then one day we heard English, native-speaker English. We had entered the SOS Hospital in Phnom Penh and Tgirl4 beamed, “They speak very English.”

Hearing staff and also a lady, who had walked in off the street, speak clear English felt comfortingly familiar – it was so nice to fully understand what we were hearing. There were other languages too, but we could pick out our heart language, the one we feel most at home with.

It reminded me how hard it must be for refugees and new migrants – and so often they have not only a language barrier, but are disempowered in other ways as well. Having to cope with trauma, displacement, loss of family and uncertainly about the fate of loved ones, no familiarity, new food, new housing, new transport, different clothing, different rituals (in short, a totally different culture), and usually with bleak job prospects, very limited finances and misunderstanding to boot. In that situation the language barrier would be far more difficult than for us as tourists-staying-in-a-comfortable-guesthouse-with-riel-in-our-pockets-and-US$-in-the-bank. We can even go home if we want to – we *have* a home to return to.

Both Cambodia and Vietnam have had their fair share of refugees over the past few decades. More often than not they were nothing more to me than fleeting television images of unwanted people. My views on them were molded more by the reporter’s disapproving tone than by any political understanding. I ask myself now, who is responsible for ensuring freedom for those who want to escape from oppressive regimes? Who will foot the bill for those who risk their lives and give up everything they know to seek out a new life of hope? I look at Real Live Faces here and wonder if these people I am passing on the street have family members out in the refugee-quota-restricted world of the west. I wonder if they tried to escape themselves. The micro-picture and macro-picture blur together as thoughts swirl round my head. To make a big difference you need the language of diplomacy, the language of international relations, language full of legalese.

But even a little language is empowering – at the end of this year, Rob will return to his job helping refugees and new migrants settle into their new lives in New Zealand. While he was always aware of the issues they face, I imagine he will now take with him an even deeper understanding. While he is naturally an empathetic person, having re-experienced the inability to communicate, he will now feel more fully and their cries will resonate more clearly for him.