if salt loses its saltiness…

Tuesday, November 3rd, 2009Krakow, Poland

There’s an object lesson in today’s expedition. A Scripture or two to reflect on. But we haven’t yet. We were too busy writing a story. Jgirl15 came up with the outline and then frantically scribbled the main ideas and some sample sentences onto paper. Together we fleshed it out.

CLANG CLANG CLANG

The operator rang a bell and the lift I shared with eight other miners descended, plunging into instant darkness, rattling its way into the depths of the earth.

”Times have changed,” I murmured with ever-present relief. We do not have to fear a slow and insecure ride to the bottom of the shaft in a hemp swing-like seat hanging off a rope as fat as my growing son’s arm. So fearful of falling to the bottom and certain death, were the miners before us, that all the way down, prayers and hymns for safety echoed, bouncing off the walls before being consumed by the darkness. Even with their flickering candles, they couldn’t push away that close darkness surrounding them.

The creaking lift and helmets fitted with torches we are using now have put an end to that. The lift, what a fine piece of technology. It always threatens to drive us occupants into the rock at high speed, but, thankfully, it hasn’t yet. It IS safer.

Down down down……..some 327 metres underground. In earlier times the miners did not go so deeply, but we have dug down to a third level now.

I start my work at 8am, using the original hundreds-of-years-old method used for mining salt. My companions and I hammer tar coated wedges into the rock. It’s hard sweaty work, but after much banging there’s an ear-splitting crack and a ten tonne block of salt escapes. It lies still, waiting to be chiselled into three or four blocks and then further chiselled into cylinders. It’s much easier to move a “log” of salt than a block – blocks don’t roll.

Despite being hard work, we proceed with enthusiasm; our wealth is in salt!

Four hundred years ago when this mine was just beginning, salt was being used as a currency. One log of salt could buy a small village – forty houses.

Before extensive mining, the white powder had been extracted from a large saltwater lake, pottery containers of water being boiled over fires to evaporate the water, leaving the precious trade-able commodity behind. But when the lake dried up, the residents of the region began digging, presumably looking for more water. What they found, instead, was salt. A Lot Of Salt. For five hundred years the area will provide both salt and work for many – over 300 kilometres of tunnels will eventually be excavated, a labyrinth extending under the whole town of Wieliczka. There’s wealth in salt alright.

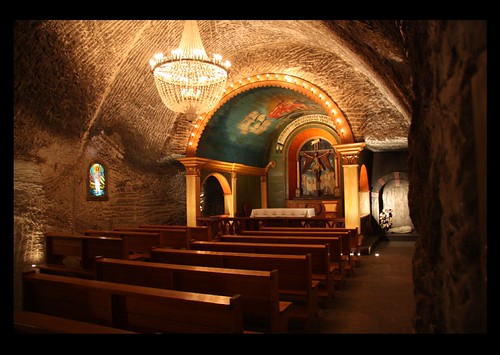

Our work comes to a halt at midday. We’re Polish. We’re Catholic. Most of us walk to the big chapel of our patron saint, Kinga. You could be forgiven for thinking the floor is polished black marble, but, just like the steps we descend, the statues of the saints, the carvings depicting the life of Jesus….they are all made of salt. Of course, perhaps. Salt gives riches not merely measured in monetary terms.

The chapel itself used to be a very large mining chamber until it was transformed into this highly decorated place of worship – actually, it’s not even finished yet. The last carving will not be completed for another half a century, until 1963. People will stand in awe under its shining chandeliers, amazed that even they are made of salt. Pure salt is white or transparent, and special pieces have been taken to create these magnificent lights. They really do sparkle against the blackness of the rest of the salt, salt coloured by being mixed with other stones, rocks and metals.

Before heading back to work I enjoy a small jelly filled with fish and vegetables. I’m rich to have a caring wife, who after years of marriage, still shows her love, making special treats to eat. It’s not that I’d mind gnawing on a poppy seed bread stick like the rest of the crew, but these little delicacies do brighten the darkness.

Strolling through the different chambers, there’s always something new to see. Today I took a different tunnel and found an old unused winch. It had points for coupling horses to, and a seat. Round and round and round the horses used to plod, hour after hour after hour. Someone had to steady their pace and initially this person, too, with the animals, would plod hour after hour after hour, round and round and round. That was before The Seat. It doesn’t look like much, but it was as desired as a throne. Everyone wanted this job – instead of having to walk at the horses’ side, they could sit, almost at leisure, a rich man.

Nearby was a feedbox, undoubtedly used by the working horses. You know what? When my Great-Grandfather worked as a miner, he helped to transport the horses. With the wealth of stories passed on from one generation to the next, I have heard how the horses were fitted into hemp harnesses and lowered into the darkness, just like the miners themselves. Unsurprisingly, plenty took fright. My predecessor, with a lifetime of handling these beasts, still had trouble calming them as they arrived at their destination. Occasionally, a horse arrived calm; usually it meant it had died of fear on the way down. Needless to say, this was no easy job. Eventually, my great-grandfather, yes one of my very own ancestors, came up with the bright idea in the midst of this darkness to build underground stables, to end the necessity of daily hoisting. From that time on, once the horses were down, they were destined to live the rest of their lives deep underground. I can imagine hearing the hooves clip-clopping along the salt floors. I prefer not to think of the smell, the heat generated by so many men and animals in such confined spaces.

These days all that is left of those times are the impressive chapels, enormous old winches, crystal-encrusted ladders and tools, some of which are still in use. My favourite would have to be the wooden cart on wheels that is run along a track up and down the inclines – to prevent too many chunks of salt falling out, the front was designed higher than the back. It’s amazing to think that you’ll still be able to see these carts with their original wooden boards in another hundred years’ time. You could even say salt preserves memories.

I return to the chamber, where I’ve worked all my time. In the entire history of the mine, every single miner has worked in the very same chamber that they started off in, never changing to another one. Why would you leave a job undone? Sometimes even a few generations work the same chamber. It was – and is – a long slow task. Some say it must be tiring to always be working hard, monotonous to always be doing the same thing day after day, but it’s a special job, and seeing the cavern emerge out of solid wall makes it all worthwhile. Watching the carvers create birds clinging to the ceiling or monks kneeling at a cross or beautiful angels brings me a satisfaction I could not find anywhere else.

Besides, it’s a safe job. I could be mining coal or iron – in unhealthy dangerous conditions. At least I’m not breathing substances that can kill me. I can lick the walls here and it does me no harm! One could even argue it’s beneficial – I mean, we do use salt for preserving our meat and vegetables, and we gargle it whenever anything ails us. It’s funny to think of licking the walls, but I’ll tell you something. In a hundred years’ time people will be descending the same shafts, walking through these tunnels, these chambers, and clambering up the stairs, escorted by tour guides, who will inform them they may lick the walls, but not the carvings. And they’ll do it! Good thing salt kills germs, I say.

I work the afternoon.

I don’t lick the walls.

I take the lift back up again, hurtling through the darkness, towards the outside darkness which blankets our town by mid-afternoon in the winter.

CLANG CLANG CLANG

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOME RANDOM FACTS, WHICH DID NOT MAKE IT INTO THE STORY:

- the mine is kept at 14 degrees celsius year round – which makes it much warmer than the outside temperature for most of the year, and cooler in summer

- every miner is (and has been from the beginning of the mine’s existence) issued with a special uniform. In times past they were also given decorated ceremonial axes; now they are given something else instead, which the tour guide told us, but which none of us can remember the details of!

- way back at the beginning of the mine being dug, hooded men would crawl through the tunnels carrying long poles with a fire on the end of them. It is believed the fire would burn up pockets of methane, ensuring the tunnel would then be safe for other miners to proceed into. Of course, this was a dangerous – or even deadly – job when a large amount of methane was encountered.

- when the miners had tallow lights, it made the black salt appear green, and so the salt was called, for quite some time, green salt.

- some of the salt crystals are perfect cubes.

- there’s a museum to visit at the end of the mine tour, but it was not mentioned by our particular guide. Like the mine tour, you are required to go through with a guide, and although they do hurry you through the exhibits, we would highly recommend the museum to anyone, who happens to go there. It was a pricey day (although a lot cheaper than taking a tour from Krakow – we caught the bus out to Wieliczka ourselves), but money well spent. We had heard the mine itself was awe-inspiring, and indeed it was. But no-one had mentioned the 380 steps down a mineshaft, the three kilometre circuit you end up walking, the hunks of salt that a miner will rip from the walls and ceilings to give children to take home, the underground lakes, the pre-recorded “performances” by statues, the light shows, the winches, the whole forest of tree trunks supporting walls, the paintings, the statues of famous visitors like Copernicus and Goethe, the dioramas….it was so much more than we expected.