The Manatee Pond

Friday, February 6th, 200917th January 2009:

[long entry…]

It was past eight o’clock, and I was still waiting for Mr. Boodoo. Or rather ‘Shortman’, his sidekick, who Mr. Douglas had said would come to pick me up.

Heavy grey clouds held the promise of rain. I watched them pile up as the clock turned to eight-thirty, then ten to nine.

“Still playing the waiting game?”

I wondered what it looked like to Mr. Douglas. He’d seen me arrive with a different guy every day, and now I was sitting and waiting for half a morning—after having waited in vain for Truckman for half a day—to be picked up by yet another man.

But he knew Mr. Boodoo. “It’s odd,” he said. “He is normally on time. This is not at all businesslike.”

Mr. Douglas let me use his phone and Mr. Boodoo sounded surprised that nobody had come to pick me up. At least he hadn’t forgotten about me.

“Hold on,” he said.

I did.

*

Shortman arrived five minutes later, with two boys in their early twenties along for the ride. He apologised for being late, but he wasn’t serious. Neither was I. They were here: that was all that mattered.

“It’s Saturday,” he said. It’s our time for liming!”

And with that we were off to d’Hammerhead Bar.

*

“Look at that moth,” Shortman said and grabbed my arm. Something about his eyes made me hesitate. A moth?

I looked and my heart stopped for an instant.

It sat there under the ceiling like a painting, each wing the size of my hand. A museum-specimen come to life. Except that I knew that it wouldn’t move again until dark. With that insight, I could breathe again.

The jungle had come to the bar, and it was time for us to leave.

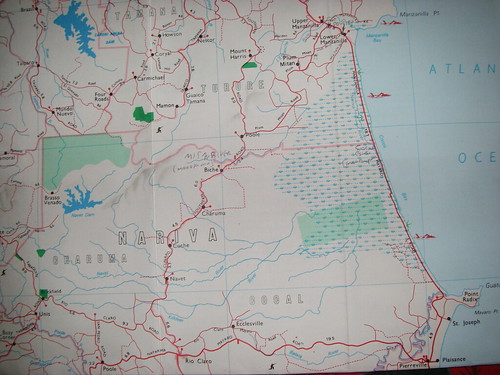

I wondered when—and if—we would meet the mysterious Mr. Boodoo as we drove up to the RAMSAR sign that marked the entrance to the Protected Area. The school-maxi driver had told me that here I would find guys who knew the swamp. The guy in question lived in a house right next to the sign. His name was Bobby.

He showed me his catch of calalloo crabs and cascadoo. The crabs sold out before we had finished lunch: a delicious curry stew prepared by Shortman who maintained that men were the better cooks.

I found these men a refreshing change from those I had encountered so far.