Giraffes

February 1st, 2007The bush around Niamey is barren and seemingly lifeless. Yet, strangely, it’s home to reputedly the last herd of wild giraffes in West Africa.

The day after Dan arrives in Niger, the two Estonians and us arrange for a taxi to take us into the bush to try and track them down.

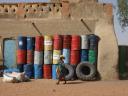

Leaving Niamey, we pass fields of litter and detritus. Niger, like every other African country, is fighting a losing battle against a rising tide of filth. Plastic bags are the main scourge, half burried in the ground like strange crops or fluttering – like giant fruit bats – from trees.

After about an hour, we stop to pick up the local guide that is compulsory for viewing the giraffes.

I ask the guide why, in the whole hugeness of West Africa, it’s here that the giraffes have chosen as their last stronghold. ‘Acacia trees,’ he responds. ‘You find them in other parts of West Africa, but here they’re particularly big and abundant – giraffes won’t eat anything else.’

A few kilometres down the road, the guide orders the driver to leave the road and plunge into the bush. It’s more dramatic than it sounds; here the bush is snooker table-flat. Importantly, though, there’s a profusion of large acacias. It looks promising.

Before we proceed any further, the guide doles out a big, fat caveat. ‘Of course, there’s a chance we may not see any giraffes,’ he warns. ‘They’re like hippos or any other wild animal: they free; they go where they please. Be prepared for the worst.’

But his warning proves unfounded. Within only a few minutes of turning off the road, we spot our first giraffes, three of them: a mother and her two children. Our guide has earned his money.

They’re a fine sight. Graceful and silent, they roam effortlessly from tree to tree, stopping at each to savour its thorny delights. They don’t seem in the least bit bothered by us, instead shooting us the occasional inquisitive glance. Other than that, they go about the serious business of eating as if we weren’t there, with the gourmand’s dedication to his food.

We move on and clock six more. This group contains a male, a real brute of an animal, at least six metres high. There’s something prehistoric about giraffes; they seem to break all natural laws of proportion and scale.

But there’s also an incredible gentleness about them. Maybe it’s something to do with their big eyelashes and docile looks. I leave the bush – and the giraffes – with a profound sense of peace.

One thing I don’t understand though: why does having a blue tongue better equip giraffes for dealing with thorny acacia trees? Answers on a postcard please…