To Timbuktu

Tuesday, January 23rd, 2007We’re back on the river after our brief detour to Dogon country. The mode of transport is a pinasse complete with 40cc Honda motor. The destination is Timbuktu, the fabled city of gold whose discovery cost so many European lives.

We’ve been joined for the three-day trip by four friends from the UK, Cat, my girlfriend, an Australian, Trev, who came with us to Dogon Country, and two other English guys and one woman we’ve met in Mopti. Strangely, the two guys, from London, are also called Ben and Dan; should make for an interesting ride…

The first bit of the trip is a straightforward rerun of our earlier ventures to Lac Debo – where readers may recall I was first hit by malaria. It’s much the same as before – peaceful, little fishing villages slipping past as we eat up the miles.

During the journey, I find myself reflecting on Mungo Park’s journey up this part of the river. By this stage, Park was a desperate man. He had lost most of his men to malaria or murder. His presence – not for the first time – had not been welcomed by many of the local kings, but Park resolved to press on, abandoning all his usual diplomacy and opting instead to fight his way down the river.

In our pinasse, with its gleaming new outboard, we whip along at a pace. How different for Park; with nothing but wind or manpower to propel his craft along, progress would have been slow. Split into narrow creeks and channels, the Niger at this point is narrow. In their flimsy boat, Park and his men would have made a tempting target for any angry tribesmen attempting to hinder their progress.

Because none of Park’s diaries from this stage of his journey survived, one can only imagine the horrors he and his men endured as they fended off attacks from the bank. The wide open space of Lac Debo, where the tendrils of the Inland Delta come together, must have come as a welcome relief to the crew of the Djoliba.

For us, it’s Lac Debo where the fun begins. Due to a late start, we’re running slightly behind schedule – as far as anything in Africa ever runs to such a thing. There probably isn’t even a word for it here. If we’re to make Timbuktu in time for our next date – a three-day festival in the middle of the Sahara – we need to be across the other side of the lake by the end of the day.

Night falls, and still we’re a long way off our target. Somehow, though, our skipper manages to plough on in the dark. And it’s proper dark here, African dark – not a photon of light pollution in the sky and, tonight, no moon.

For us passengers it’s a wonderful opportunity to lie on the deck of the boat and watch the stars, Orion doing his nightly stellar battle with the mighty Taurus. For the skipper, though, the conditions are tough.

Even at this time of night, some Bozo fishermen will still be out dredging the waters for fresh catches. Some of them have lights in their pirogues, and these we can see twinkling in the dark. But it’s the ones we can’t see that are the danger. At any moment I half expect to hear bangs and shouts as we plough across the path of a canoe hidden in the murky blackness of the lake.

But after about an hour and a half, the skipper brings us skillfully up on the far shore of the lake, with scarcely a bump. We all applaud, relieved to be on terra firma.

After a night camping on the lake’s sandy shore, we set sail early. Day two passes in much the same way as day one. We stop at a village to buy fish – the plump, fleshy capittaine for which the Niger is famous, and seems to produce in endless quantities.

Mid-afternoon, the pinasse pulls into Niafunke, a town situated on the beginning of the Niger’s Great Bend, where the river gradually begins to deviate away from its logic-defying journey north into the Sahara, to a more sensible course east then south towards the Atlantic.

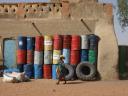

Niafunke is only small, but it’s famous for being home to the great Malian blues musician, Ali Farka Toure. Toure sadly died last year, but the town has been imortalised as the name of one of the last albums he recorded. For all that, it’s not much of a place – sandy, hot, the usual ramshackle market place, no sign of its illustrious son. We don’t stop for long, the pinasse skipper keen to push on.

Day three, I awake on the sand dune where we’ve stopped for the night with a strange thought rolling through my head: for the first and possibly only time in my life, I can say, ‘Today I’m going to Timbuktu’.