Fallen empire

Thursday, January 25th, 2007In spite of all the time, money and human capital expended, when European explorers finally reached Timbuktu, they were hugely disappointed. Although still an important centre of Islamlic scholarship, as it remains today, they found it to be a shadow of its former self.

Timbuktu’s reputation in the West was based almot exclusively on the accounts of Leo Africanus, a Spanish Moor who visited the town in 1494, and sent back reports of great wealth and culture. Indeed, when Africanus visited, Timbuktu was at the height of its powers as a great trading centre in the old Malian Empire. But ever since it was attacked by Morrocans in the 1590s, and much of its wealth plundered, Timbuktu had been a city in decline.

For us latter day Europeans arriving in this most fabled of places, the experience is pretty similar. Getting to the place is still a great challenge, much as it was for our questing ancestors, and it’s this reputation for remoteness on which the town seems to be trading today. A t-shirt being sold by one of Timbuktu’s many touts sums it up: ‘Timbuktu,’ it says. ‘Welcome to the middle of nowhere.’

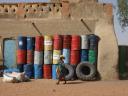

But the town itself fails to live up to they hype. Its wide, dusty streets are buried in deep drifts of sands, giving the impression that it’s being swallowed whole by the desert. Some of the architecture is interesting, particularly the impressive Djingarie Berg mosque, but much of it is like anywhere else in the Malian Sahel.

For all that, though, Timbuktu still has an air of mystery about it, mainly due to its colourful history. During the short time we have in the town, I fulfill a personal pilgrimage by visiting the old homes of Gordon Laing and Rene Caillie, two of the European explorers who actually succeeded in reaching Timbuktu.

Laing made it here and stayed a while but never made it home after he was ambushed and murdered by a group of Tuareg nomads as he tried to leave the town. Caillie, on the other hand, became the first European to reach Timbuktu and return to tell his tale.

Neither of their homes are much to look at now. Caille’s has been rebuilt and is closed to the public. Laing’s, on the other hand, looks pretty much as it would have to him, with crumbling mud walls and heavy wood and iron-studded door.

The door is ajar, so I decide to have a poke around. On the other side, the rooms are pretty much empty. Two startled looking men emerge from one of them, a pissed off ‘what they hell are you doing here’ look on their faces. I apologise, attempting to explain myself, but I wonder if they know or even care who Laing was.