Wash my soul

April 24th, 2008

During the French revolution some demented aristocrats insisted on lying face up, so they could see the guillotine blade coming down. Look death in its gleaming eye. Meet it, uhm, head-on. Confront and embrace the final moment.

I think I would be of that persuasion.

Sitting on an Indian government bus, right in front, I was morbidly fixated on the road, or to be more precise, my oncoming death. The bus was on the wrong side of the road, the driver trying to overtake the vehicles in front. Ahead, a lumbering Tata truck was charging towards us. Instead of swerving back into his own lane, the bus driver took a drag on his beedie and started blasting his horn, as though that would miraculously make the truck go away. It was an exercise in uneasy anticipation, like watching an engine disintegrate from the window of a plane. The truck responded with its own roaring wail and was obviously staying put on its side of the road. After all, it had the extra fury and protection of “CHRISTâ€, the name emblazoned in 2 foot high decorated letters, attached like a fanning tiara above the cabby of the truck. So, this is how I would die. Colliding head-on with a truck called Christ. As a devout atheist, the pertinent poetic justice wasn’t lost on me…

A fraction of a second before impact, the bus driver must’ve lost nerve and veered the bus back onto our lane, causing a car to hurtle off the road to make way. The truck missed us by half an inch, and I could literally feel the brush of death as the force of the slipstream hit me in the face.

This suicidal game of “chicken†was repeated throughout the journey, the goal being to see how many vehicles they can scare off the road. The trucks seem to come out the winner most times, having the reputation as being the biggest and mightiest on the road, and consequently, the most reckless. Each truck was brightly painted with intricate designs, the cabbies festooned with garlands, beads and pictures of the driver’s chosen gods and gurus on the dashboard. With its profusion of gods, religions and shrines it’s no wonder Kerala’s tourism board came up with the slogan of “God’s own countryâ€.

It didn’t take long before I was broken-in by the reckless driving, and I found myself nodding off with near-death-experience fatigue. I looked out the metal bars of the bus window, snapshots of roadside life flashing by. Women gathering around a well, balancing aluminium pitchers on their heads; men swarming outside a toddy shack, selling the lethally strong home-brew made from coconuts. The late afternoon air was screeching with crows, the cockroaches of the Indian sky.

Che Guevara, eternally trapped as the same black stencilled face, gazed from hand painted billboards along the road. The hammer and sickle (another communist emblem in serious need of updating) dotted the landscape, along with jewellery advertisements, displaying photos of uncommonly fair-skinned Indian girls dripping with gold, and smiling coyly under the slogan: “Purity is our Heritageâ€. Unlike other parts of the world, it seems that chastity, not sex is used as a subliminal marketing tool. Beefy, moustachioed politicians grinned from CPI (Communist Party India) posters, some with eyes scratched out or simply slashed to tatters by the dissatisfied electorate.

Kerala made history in 1957 as the first state in the world to democratically elect a communist government, which has governed the state in regular intervals since then. It can boast a pretty impressive track record: The literacy rate (91%) is the highest of any developing nation in the world, the lowest infant mortality in India, and the most equitable land distribution policy of any Indian state.

But an article and macabre photo in The Hindustan newspaper spoke of another reality. The previous day, dozens of men and women protested against the closure of a local factory. The men were all perched in trees with nooses around their necks, the women below, each brandishing a little petrol can. If the cops dared to move closer to disperse them, the men instantly made a move to jump off the branches, nooses tightening, and the women lit a match, ready to turn themselves into human bonfires.

The article exposed the darker underbelly of the glowing communist statistics: the lack of industrial development and foreign investment in Kerala, the high unemployment and crippling debt amongst farmers, the highest suicide rates and liquor consumption in India.

1.5 hours later, the bus dropped me off at Alappuzha (Alleppey), a town situated in the Keralan Backwaters, made famous in Arundhati Roy’s Booker Prize-winning novel “The God of Small Thingsâ€. Only planning to stay for 1 night, I headed to the nearest hotel sign I could see, the Raiban Annexe Hotel. This was definitely one for the homeboys. No candy-striped hammock or yoga flyer in sight. The wraparound balcony heaved with young Indian men leaning over like palm trees, their oiled black hair glistening in the sun.

A figure stirred behind the murky shadows of the reception. He looked like a cameo actor in a David Lynch film. Dwarf-like, bulbous head, his bulging eyes a psychic pale grey.

He took a key, and a lock the size of a toddler’s foot, and shuffled up the stairs.

“Wait hereâ€, he disappeared into a cupboard, and emerged with a sheet and pillow case.

The cavernous room displayed the familiar decor of mental-institution-chic. Cadaver-white walls wrinkled with cracks, bruised with the blemishes of human habitation. Two single beds shoved together, like a pair of worn out mules, tired and forlorn after carrying too many human loads. On each, the remains of two pillows, brown and split open, their disgorged insides spilling out in a grey mess. With the resoluteness of a coroner, he scooped one up and deftly slipped over a pillow case, covering the unsightly evidence. He threw the single sheet over one of the beds, shrouding the mattress.

I took the room. All that’s needed is a thin layer of linen separating you from the nightmares and stains of those that came before.

Taking a walk round the gritty centre of town, I was struck by the neck to neck jewellery shops lining the main street. It seems that the poorer a town, the more gold shops it has. The biggest building in the street, towering above the Hindu temple was a jewellery emporium, a beggar prostrating himself outside the gaudy roman pillar entrance.

The next morning I boarded the ferry plying the backwaters between Alappuzha and Kollam. The area, known as Kuttanad, is sandwiched between the sea and the hills, and comprises a bewildering labyrinth of canals, rivers, rivulets and lakes.

It was a whole day’s journey, with the option of getting off midway at an ashram.

I grabbed a seat on the upper deck and perused the rich, tropical tapestry of this uniquely Keralan landscape. Water forms the main leitmotif in the timeless still-life of the Backwaters. Pupils in bright blue uniforms going to school by canoe; women, in clinging saris washing themselves and their clothes at the water’s edge; children sitting on and washing a muddy buffalo; pelican-legged men, lungjis folded to above the knee, collecting oysters while steering their canoes with bamboo poles.

The boat stopped for lunch at a typical “meals†restaurant, a type of canteen style place dishing up the staple Indian lunch of Thali, served on a banana leaf and eaten with your hands. Sorry, your right hand, the left hand hangs limp by the side, used only for washing the nether regions. Thali consists of a heap of rice surrounded by small dollops of fiery chutney, pickles, and watery veg curries, served with a chapati. There’s something liberating about getting down and dirty with your hands, breaking all the rules of table etiquette instilled in us since childhood. I have to admit though, I’ll probably stick to the more sensible spoon, I ended up getting more grub on my face and hair, than in my mouth.

Back on the boat, and a beer later, I was met by a startling vision. On a slither of land between the sea and the backwaters loomed two icing-pink high rise tower blocks, in flagrant disregard of the unwritten Keralan law of no high buildings. They’d look more at home on a London council estate than amidst a coconut palm forest. One of the passengers informed me that this was the ashram of the renowned female spiritual megastar, Sri Amritanandamayi Devi, mercifully known as Amma (mum) or “Hugging Mamaâ€. Thousands of visitors flock here every year to receive one of Amma’s famous, life- transforming hugs. Regarded less as a guru, than an embodiment of selfless love, she spends a lot of her time travelling around India and the world, holding marathon hugging sessions. Always intrigued by what I don’t understand (which is just about everything), I decided to hop off at the ashram.

Since Allen Ginsberg’s drug-fuelled visions in Varanasi, and the Beatle’s publicity stunt with an Indian Yogi in the 60’s, there has always been a constant stream of spiritually parched Westerners to India, in particular South India, which boasts the highest concentration of ashrams.

For those in the spiritual dark, an ashram is a community where people work, live and perform devotional practices together (some people have quite a wide interpretation of ‘devotional’) usually drawn by the charisma (or marketing machine) of a ‘holy’ person, also known as a guru.

The check-in desk for visitors was up a flight of stairs, past rows of seated ashramites, industriously folding pamphlets and putting them into piled up boxes. The guy working at reception had sunken in eyes, watery and pallid, and a patient smile.

“I’m afraid you’ve just missed Amma. She left yesterday on her 2 month tour of India.†So no cuddle for me then.

The cost for one night’s board and lodging was 150 Rupees ($3.70), whether you’re staying for one day or several years. He handed me a form to fill in. Under ‘Spiritual Name’ I nearly put down ‘Barbie’ or ‘Debbie’, but keeping my juvenile, subversive tendencies in check, I drew a dignified Х . Under ‘Occupations’ (a nice variation on the usual singular form) there were several numbered lines. As someone who thinks you should try more than one career in life, I didn’t have any problem filling those up. 1)English language conquistador, 2)Adviser to refugees and asylum seekers on how to colonise the UK 3)metal clothing and bodily armour blacksmith.

I took the lift to my room (another oddity you don’t expect in an ashram), situated on the 15th floor of one of the single-gender accommodation blocks. The views from the top were spectacular. On one side, the Arabian Sea breaking in long, even lines along the beach, on the other, the shimmering highway of the river, cutting its way through the dense palm canopy.

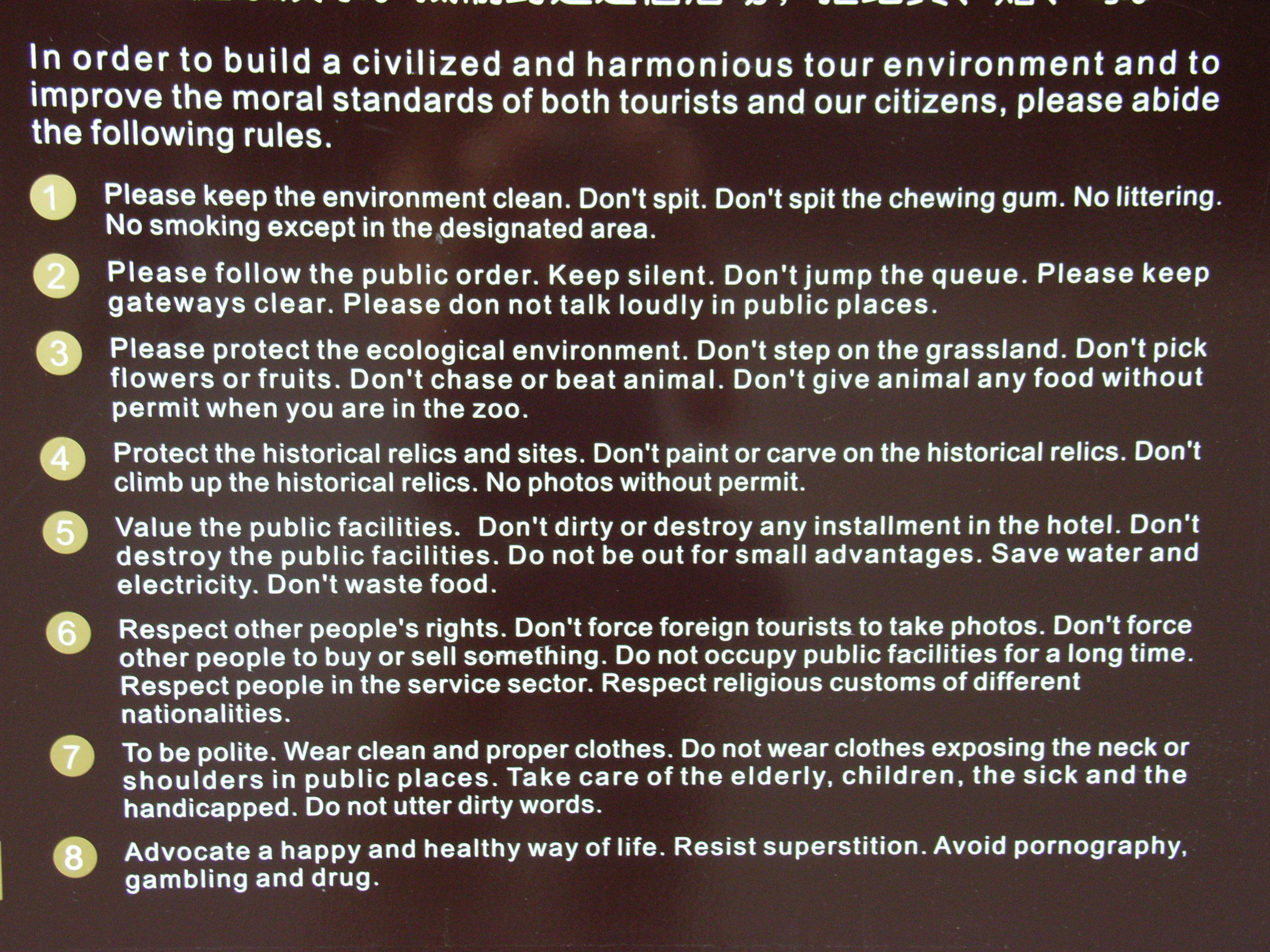

Someone else was already staying in the room, her clothes hanging on a line strung between the barren walls. It was basic but adequate, no furnishings except 2 vinyl-covered mattresses on the floor. A Western toilet and cold shower completed the facilities. The only wall décor was a notice stipulating the code of conduct while staying at the ashram:

1)Refrain from public displays of affection. Hugging, kissing, holding hands etc is inappropriate. (Quite ironic, since Amma’s fame is based on hugging and kissing; male and female alike.)

2)Cigarettes, alcohol and drugs are strictly forbidden, both on and off the ashram premises.

3)Please wear clean , modest clothing that covers both the arms and legs. (yeah, the weak spirit needs to be shielded from those fleshy limbs!)

4)Observing silence and minimising speech keeps us focussed inwards.

5)Do not go to the beach and teashops after sunset.

6)Visiting the Ashram neighbourhood is not advised. (WHY?? Is it because the noisy, real life out there might unsettle the inwardly focused, sensitive spirits of the ashramites?)

It kinda felt like a cross between a boot camp and a nunnery. I was already craving a g’n’t.

So to take my mind off such contaminated thoughts, I joined the daily introductory tour along with the other new arrivals. We were shown a video about Amma’s life, the tearful and emotionally charged hugging sessions , her humanitarian work and the many prestigious awards she’s received for her charitable initiatives. Even a die-hard cynic like myself was impressed by the fact that she tucks in her sari, sets aside the meditation cushion and gets out into the community. She donated a whopping $25 million to the tsunami victims, and funds and builds homes, schools, universities, hospitals, refuges and orphanages throughout the country. It was a refreshing antidote to the well-publicised scandals of new age gurus preying on gullible foreigners (and locals) and using their money to boost their collection of luxury cars or espousing useless teachings about astral planes, liberation through group sex, and the like.

After the tour, the guide rushed off to the evening chanting session, taking place in the main temple. Similar to a monastery, the daily life of the ashramite is segmented into a neat timetable of spiritual practices, starting at 4.50am with chanting the thousand names of the Divine Mother. The rest of the day is filled with meditation, meals and Seva, or selfless service. This includes preparing and serving food, cleaning, sorting out rubbish or any service needed by the ashram. Although not compulsory, visitors are expected to put in a few hours of voluntary service.

Supper was served in a huge hall where ashramites and short stay visitors eat together at round tables dispersed throughout the canteen. A free meal of curry and rice is served from industrial sized pots, but getting a bit weary of slodgy thalis and curries, I opted for the “Western†canteen, where delicious and cheap pizzas, pastas and veg burgers were served.

I went to sit down at a table occupied by other ashramites, stooped over their stainless steel bowls. I looked around. All ages, nationalities and races were represented, and I could make out a Babel of different languages drifting softly from each table. The devotees distinguished themselves from the short-stay fodder by their all-white, flowing garments, with here and there a wooden bead necklace as the only decorative indulgence. Opposite me, the woman’s tight, pale face bore no trace of make up but was liberally powdered with devoutness. The conversation was white-washed with the dull neutralities of undecorated speech. I felt like I’d gate-crashed an exclusive party and everyone knew, but they were too polite to tell me to leave.

I was dying to ask them some questions: which modern comfort they miss the most, where they get the money from to be able to live without an income for years, if they’ve ever broken any of the ashram’s rules, whether they sometimes fancy each other, and if so, what do they do about it? But fighting my Tourette-like syndrome of blurting out inappropriate questions/comments, I asked them about Amma’s hugs, and what they felt when she hugged them. Their enthusiasm about this subject immediately animated their faces, clearly happy to share their experience. They all claimed to feel an overpowering sense of warmth, love and serenity. They felt that Amma has the innate ability to delve into their deepest being, through the simple act of a hug. One Dutch girl at the table told me that while Amma was giving her a hug, she whispered her pet name, a name she hadn’t been called since childhood.

“I was like, Oh my god! How did she know that! She’s incredible, after she hugs you, you’re glowing with love, you just stand there like… Wow!â€

Later that night I asked my room mate, Ivanna, why she decided to become a devotee and leave her life in Switzerland behind.

“I was sick of my party life, you know. I used to go out a lot, take drugs, and all that stuff†her mouth curved in a frail, sad smile. Ivanna had one of those open, angelic faces, so prized by shampoo and sanitary towel advertisements. The disparity between her Snow White exterior and wounded interior made her story seem more poignant.

“I wasn’t happy, so I started looking for something more fulfilling. I found Ammaâ€

She divulged that her parents don’t support her new life, thinking she’s joined a cult in India. “They will never understand. But that’s OK, cause I don’t understand them. All I know is they’re not happy, so they can’t tell me how to live my lifeâ€

Under her veil of devotion to Amma and her new spiritual path, Ivanna concealed a streak of defiant individuality, which I liked. She had her reservations about wearing the shapeless, baggy pantaloons and knee-length shirts, nearly missed the curfew a few times, and commented on the unnatural separation of the sexes in the ashram, as well as Indian society in general. I might be wrong but it seemed that she was looking at her stay in the Ashram as a penance to be served out rather than something she wholeheartedly wanted to do.

The next morning I ventured out to the beach area which was humming with activity by the time I arrived. Not the usual fun in the sun amusements associated with beach life, though. A tone-deaf hippie was sitting as upright as a governess, chanting Ohmmmmm. Another human pole was pressing forefinger and thumb against his one nostril, while snorting loudly through the open one. Sitting crossed-leg, a girl was thrusting her pelvis forwards and backwards in a rhythmic trance. A distance away, set back in the dark shadows of the trees, the more corporeal activity of voyeurism was taking place. The spiritual, mental and physical exercises of the Westerners was a peepshow for the young Asian men, eyes firmly locked on the lithe female bodies moulded in various yoga postures.

Keen to break the segregative ashram rule of not “visiting the neighbourhoodâ€, I walked to the nearest village.

A woman was kneeling by the river washing clothes. Scrubbing the stains. Beating the dirt out with a wooden bat. Maybe we do the same with our spiritual fabric. We want to wash our souls. Get rid of the spots of regret, the blemishes of experience, smears of self doubt, the stains of hurt. So we go to ashrams, meditation retreats, shrinks, self-help gurus. The launderettes of soiled souls. But the problem with human nature is that we’re stuck with it, and no amount of soul cleansing (what others call ‘soul searching’) will make it spotless again. The outward cover of white clothes, a calm composure or a serene expression is merely a clean, white pillow case which we slip over our tainted, messy insides.