Jordan 1 – Petra (Part 1)

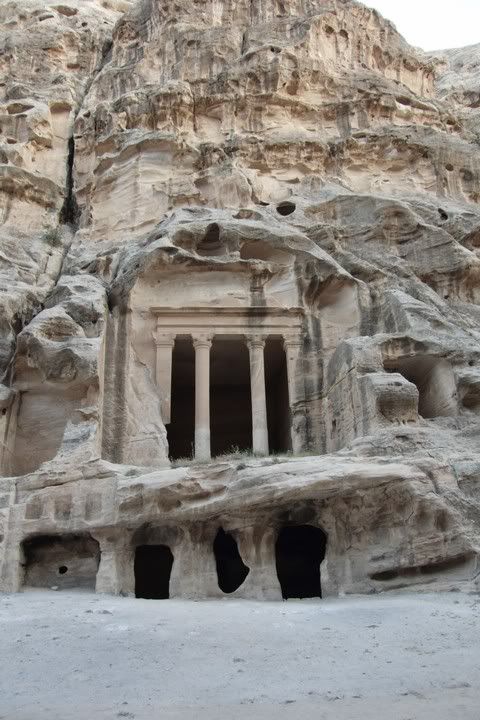

Caves and building from Little Petra

Next up after Egypt was Jordan to see the ruins of Petra (also known to some of my readers as the backdrop from Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade). The border crossing between Egypt and Jordan is one of great debate. There are two ways to go: a ferry between Egypt and Jordan on the Red Sea or a land-crossing from Egypt, into Israel and then into Jordan. Theoretically, the ferry is the best option as you avoid the dreaded Israel stamp in your passport. Why the problem with the Israel stamp? Because if you’ve been to Israel a person is generally precluded from entering any other country in the Middle East with the exception of Egypt and Jordan with whom they have a treaty. So…if I were planning to head to, say, Syria I couldn’t if I’d previously been to Israel. It seems like a no-brainer…take the ferry. Unfortunately the ferry runs on some crazy schedule where it may run 6 to 8 hours late or it may not run at all. In my case, I didn’t care about the Israel stamp as I do not intend to return to the Middle East on this passport so I opted for the land crossing which was a smart decision as I was checked into my hotel by 6 pm on Sunday…everyone who took the ferry that day didn’t arrive until after midnight.

Ahh Petra…the incredible old city tucked into the desert of Jordan and only recently rediscovered by a Swiss adventurer in 1812. Like many of the archaeological sights in the Middle East, Petra has been inhabited and occupied by several different groups over its centuries of existence. In prehistory, the region of Petra saw some of the first experiments in farming and served as an important route between the great ancient powers of Mesopotamia and Egypt. The first significant mention of Petra occurred in the Old Testament as the Israelites approached Edom after their forty years in the desert. Contrary to geographic evidence, the local legend maintains that in the hills above Petra God ordered Moses to produce water for the Israelites by speaking to the rock. Moses instead struck the rock and the spring that gushed is today named the Spring of Moses (which is now marked at the entrance to the modern village surrounding Petra: Wadi Musa). Over the following centuries possession of Petra changed hands from Assyrian to Babylonian to Persian and this instability ultimately led the way for new people to claim the area of Petra as their own.

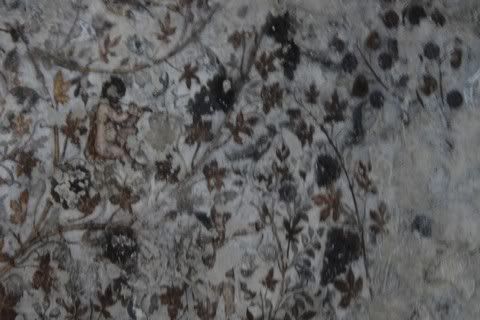

Paintings on the ceiling in Little Petra

More ceiling paintings

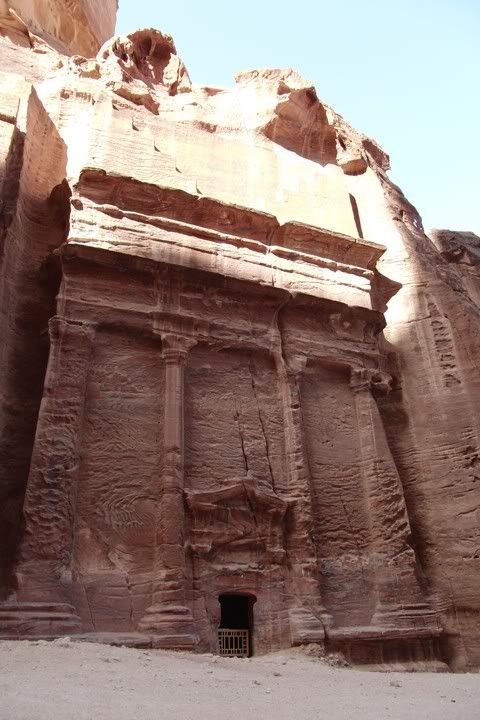

A tomb

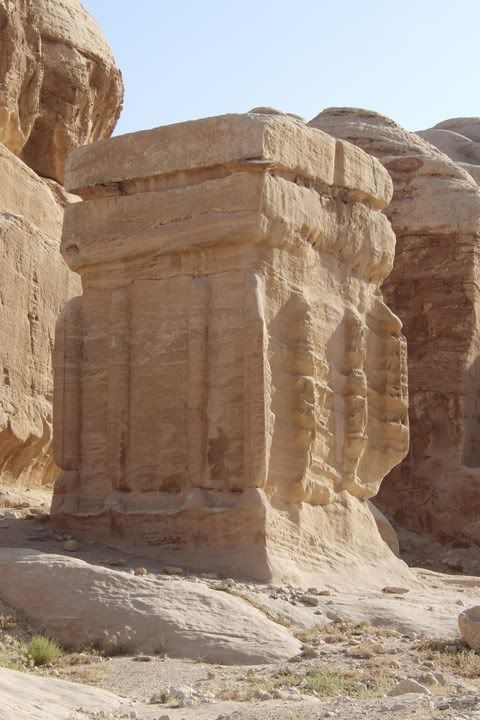

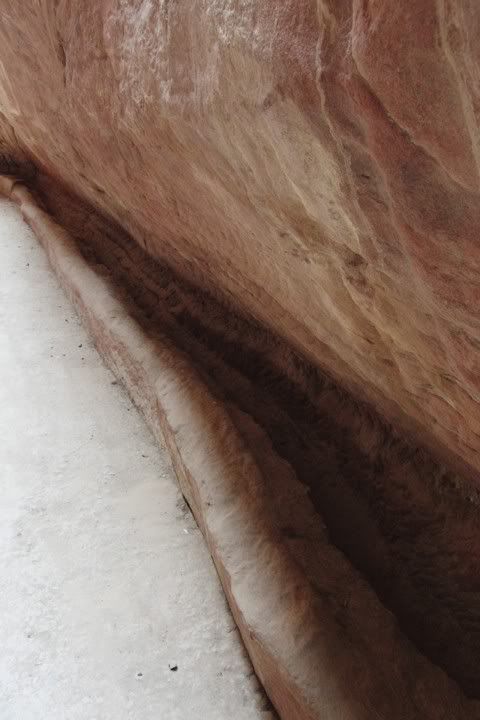

Example of the rock coloring in Petra

Much of the existing architecture in Petra is attributed to the Nabateans, a tribe of Bedouin nomads who previously inhabited northern Arabia. The traditional occupation of the Nabateans was to raid the plentiful caravans that passed through the Petra valley en route to other parts of the ancient world. Ultimately the Nabateans gave up this endeavor in favor of charging the merchants they previously plundered for safe passage and used the area as a place to do business. For several hundred years the Nabateans successfully defended their position and became wealthier and wealthier from their profits from trade of items such as copper, iron and Dead Sea bitumen (used for embalming in Egypt) as well as spices and other commodities. During the 1st centuries BC and AD, Petra was at its zenith with a population of 30,000 and was a thriving, cosmopolitan city. Of course, things were not to last…with the discovery of other trade routes by sea, Petra began its slow decline and ultimately fell into the hands of the Romans.

Under the Romans, Petra became a principal center of the new Providincia Arabia and underwent something of a cultural renaissance with the theater and the Colonnaded Street both renovated. During the 2nd and 3rd centuries things started to fall apart though and by 300 Petra was in serious disrepair. A massive earthquake in 363 sealed the deal and flattened about half of Petra. Still there were a few hangers-on until another massive earthquake in 749 destroyed the rest of the city and nearly everyone remaining were forced out. The Crusaders occupied a few small forts in the area but these were inconsequential and as far as records go, the last person other than local Bedouins, to see Petra was in 1276. It would be more 500 years before anyone else would see the city of Petra.

In 1812 under Arab disguise, the Swiss explorer Jean Louis Burckhardt entered the Siq (the long canyon entrance to the city) with a local guide. From that moment forward, Petra was no longer a secret and tourism was launched in Petra. Still, Petra was far off the beaten track and difficult to get to until the 1980s when a regular bus service was launched from Amman. It was in the 80s that the Jordanian government realized what a cash cow they had in Petra and they ordered the relocation of the local Bedouins who occupied the caves and buildings within the city to a concrete block village about 4 km away where they were provided with free housing, education, electricity, etc. I have much more interesting information on the local Bedouins to come but will save that for another post. The pictures here are largely from Little Petra which is a smaller settlement I went to see the first night as well as a few random shots of the sandstone and various artifacts around the site. The bulk of the buildings and descriptions in the main sections of Petra show up in the next several posts.

Some caves

Some camels

A jinn-block (likely for protection of the water supply)

Some of the original cobblestone through the Siq (more on the Siq in Part 2)

A gutter along the road through the Siq

Sunset

Tags: Jordan, Nabateans, Petra, Wadi Musa

Leave a Reply