Looking For A Silver Lining

Tuesday, November 29th, 200528 November 2005 (Monday) – Potosi, Bolivia

It turned out being cold was the least of my problem. I spent the whole night unable to sleep due to the combination of 2 problems.

First, creaky squeaky wooden floorboards. I never really felt they were a nuisance in other hotels, but gosh, the wooden floorboards along the corridor of this hotel were terrible, and I swear, the portion right outside my door made the worst creaky squeaky sounds! Plus the hollow thumping sound of footsteps on wood, impossible to sleep! Usually, perhaps, it would not be a problem for right around midnight or so, if most guests had gone to bed and did not visit the toilet often, it could be rather quiet in the hotel.

But no… the second problem at hand, melodramatic teenagers. At around 9pm or so last night, a teenage girl had burst out from her room, sobbing away, accompanied by her friend, shushing her. About an hour or so later, I found her still crying away in the toilet, with attempts from more friends to console her, some she tried to push away. She even ran to puke into the toilet bowl. Right. Throughout the night, doors got slammed, people were walking or running along the corridor, up and down, down and up, calling out for this or that person. I heard dramatic tearful phrases, obviously copied from the telenovelas (TV soap operas) watched and adored by these teenagers… “¡Quiero gritar!!… sob sob…” (I want to shout!), “Déjame en paz, déjame… sob sob…” (Leave me in peace, leave me…) I checked the time. 2:30am. Please, can tear ducts really last from 9pm til now?? Gimme a break!!

Later, someone shouted at them, “¡Callate!” (Shut up!”) followed by some long speech and after one final door slam, peace and quiet reigned for… hmm… 40 minutes or so, before the same door-slamming, hurried footsteps, moanful sobs, squeaky floorboards continued their renewed saga.

I packed up and left early next morning to another hostel just 20 steps away. I checked this time. No wooden floor boards. No teenagers. Perfect.

At 9am, I was picked up for my silver mine tour. In our van were Nina from Germany, Nicki and Rem from The Netherlands. All 3 were very, very tall. I had read that in these silver mine tours, sometimes, the tourists had to crawl along holes merely 1 metre high, in absolutely horrendous conditions. But Oswaldo, our guide, assured us that for the silver mine tours from this company, he had selected a mine that had the best safety records, not only for its tourists, but for its employers as well. He said the miners are humans, not animals, they need to be respected as well. While there are still some mines functioning in awful, ancient conditions, all for profit, with no considerations for the safety and health of the miners, the mine we were going had proper working shifts, better equipment for drilling holes, etc…

We put on rubber boots, wore protective clothings and were crowned with a helmet with a lamp each. At the miners’ market, we pooled together some money and bought coca leaves, bottles of gassy drinks, gloves, a pack of cigarette, toilet paper – gifts for the miners. Then, we headed to Cerro Rico, the mountain discovered 460 years ago to contain tonnes and tonnes of silver, making Potosí so rich, as to be one of the richest cities in the world at that time. Imagine! Unfortunately, the good silver lodes ran out and Potosi was left a ghost town. Later, other metals like tin, zinc, etc… were mined, rescuing Potosi from a certain death.

Today, mainly zinc and silver are mined due to the good prices. Tin, not so much.

Oswaldo informed us that the workers here earned different salaries based on the different types of work they do. They choose their own profession. No one is forced to do any job that they do not want to. Those with the lowest salaries work on separating the rocks from the minerals. Those somewhat in the middle pay-scale, work at collecting the rocks from the mines, pushing them out in wagons. Well, the wagons, on their own, weigh 500kg each. With the rocks, they weigh 1500kg. Some work! The highest-paid guy is of course the one with the toughest work and with the most health risk. He is the guy who drills the holes into the rock walls, inserts the dynamites, lights them up and walks away whistling. For him, he works perhaps just 4 hours a day. But really tough, carrying the 65kg air-compressor drill, breathing in all the dust kicked up by the drilling and the toxic fumes.

We followed Oswaldo into the tunnel. This company had spent the extra money to make the tunnel tall enough for a walking human. In some other mines, there are up to 1,500 mines in this mountain, the holes are small, just for crawling, because the company did not want to waste resources to make them any bigger than ‘necessary’.

At one spot, we climbed up 4 ladders to find 2 miners who had just finished with drilling holes to put dynamites. The guys were covered in wet mud. This was because they used air-compressor drills that came with water spray to settle the dust. In some archaic mines, they still used air-compressor drills without water spray, exposing the miners to more health risk.

The area up was a little scary, small, dark and claustrophobic. Nicki abandoned the climb halfway as she said she felt really awful. This is just one level. After they have blasted a certain distance and collected the rocks, they would have to blast upwards to create another level – another 4 ladders to climb. Imagine, if the air-compressor drill did not work and the guy had to get it changed, he had to lug this 65kg drill on his shoulder and balance himself down the ladders to bring it out of the mine.

Oswaldo led us to a section where we found another maestro (teacher). A maestro is the guy who is in charge of drilling the holes. He earns 1,800 to 2,000 bolivianos (about US$225 – US$250) a month. An average salary for the Bolivians, Oswaldo told us, is about 500 bolivianos (US$63). So, this is really good salary for the number of hours he puts in a day, up to 4 hours.

We stuck toilet paper into our ears to protect our hearing as the maestro drills between 9 to 15 holes around the wall. The holes are made centre, high up and low down, and the maestro had to support this heavy drill throughout the process. As he aims for a new hole, with nothing to support at first, his assistant needs to hold the drill at the drilling end with his hands for a short moment. Scary!

As I had said, for the maestro, his job is to drill, put the dynamite and light them. His job is thus done, and he does not care about the aftermath of the blast. The air-compressor drill is about 1.2m long. So, each day, after blasting a hole 1.2m deep, he leaves and returns anew to a new wall and blast another 1.2m.

But they do not call him a maestro for nothing. No point blasting holes just to collect the rocks, hello… He has to sniff around for the minerals. Sometimes, when they are searching for new lodes, they need to blast anywhere just based on hopes and guesses. If they blast 10m and still find nothing, then all the investment had been wasted. Other times, the maestro is blasting by following the lodes of the minerals.

Also, when they reach a certain point of security, and even if there are still more lodes to be exploited, they cannot proceed further, as any more blasting, might risk the collapse of the mine.

I cannot believe that they had been exploring the same hill for 460 years since the Spanish conquistadores discovered silver here. There are 1,500 mines here, with 10,000 miners working. Yet, they are blasting down kilometres of tunnels in any direction whatsoever. And there is a huge competition amongst the miners to get to the lodes.

It reminds me of the Egyptian pharoahs who had their tombs built in Valley of the Kings for years and years, without a clue what was the labyrinth of past tombs and tunnels like. Sometimes, the men making the tunnels would break a wall and discover the corridor of another tomb from 200 years earlier. Whoopsee. So, they had to sweep the dust up, patch the wall back and er… make a right-angled turn, to say, the left and continue chipping away with their chisels. The same might happen here as well, albeit with slightly better technology.

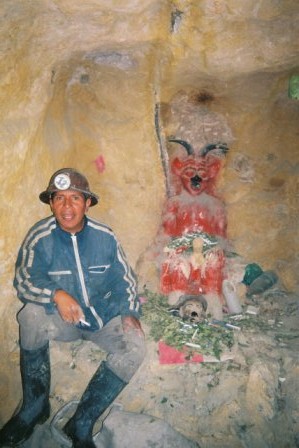

We paid a visit to El Tio (The Uncle), the god for the miners. It is a red devil-looking creature with horns, a mouth with protruding lower lips where cigarettes are laid, and a huge, huge, erect penis. Miners put coca leaves and cigarettes to ask for a successul day of finding minerals and no accident. Or perhaps, to have a penis like El Tio’s. As I had learnt from the Coca Museum in La Paz, coca leaves were used since the Spanish colonial days to help the miners last longer, through the tough conditions, the hunger, the heat or the cold, of working in the mines.

Once a year, they celebrate their own Carnaval. It is a day where the miners really do not work, and they put decorations all over El Tio and get absolutely pissed-drunk. Oh, here, they drink 96% alcohol because it is cheaper and because they are macho men.

At one point, Oswaldo asked us, as he switched off our lights, what was the most important equipment in the mine. The helmet? The boots? Nah… light, of course. With no light, one is totally left in the darkness, pure pitch-black darkness. Hence, the miners all work in pairs, just in case, one of their lights fail.

We found more miners shovelling up the rocks into the wagons. These guys were perspiring fiercely in this hot condition and due to the hard work. Yet, when they push these wagons out of the mine, at 4,000+m above sea level, it can get pretty cold outside, especially at night. So, these hot and cold spurts, what do they do to their nerves?

OK, back to the maestro. He was now inserting the dynamites into the deep end of the holes, leaving the tails hanging out. His assistant used a vacuum machine to suck up ammonium nitrate, mixed with diesel, and this mixture was blasted into the holes with the dynamites. This chemical is used to make the blasts more potent.

Meanwhile, the foreman, whom they called El Presidente and who had a wad of coca leaves permanently stuck to the insides of his mouth, was making final checks, to make sure the rest of the miners were out of the mine. The maestro proceeded to cut the tails of the dynamites into different lengths, the shortest in the centre, the area around the centre, a little bit longer and the top, bottom and extreme sides, the longest. The idea is to blast the centre portion first, and the surrounding areas next.

“¡Fuego!” (Fire!), the maestro asked from Oswaldo and he proceeded to light the dynamites’ tails one by one. We were so ready to leave the tunnel now. Oswaldo led us towards the exit, but paused at one point. We stared at him, wondering W-H-Y? and “BBBBOOOOOMMMM!!!!!!!” Nina screamed. Nicki cursed. I smiled secretly. Gosh!! The blasts had gone off when the miners and us were still in here. My goodness, you could almost see the sound waves move through the tunnel as each of the blasts exploded. Our protective clothes vibrated with the sound waves. I stared in absolutely delight all around, despite being deaf now. Incredible! Oswaldo gave us a laugh and truly led us out this time. Ah, finally… Sunlight!!! Fresh air!!!!

Life in the mine is really tough. We really respected the miners. For the maestro, soon, he would die from a poisoned lung disease. He is well aware of this. But while he is still alive, he is earning good salary for himself and his family.

I guess I would never look at silver, or for that matter, any sort of minerals in the same way now. I will really treasure my earrings which I bought from Santa Cruz. I showered, but I could not get rid of the faint smell of minerals.